Study background

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are increasingly becoming a public health challenge, particularly in resource-limited settings, where there is limited access to preventive care, early detection, and health literacy. Nevertheless, there is an immense potential of digital technologies to contribute to the enhancement of overall community health. Similarly, the WHO PEN Disease Interventions for Primary Healthcare in Low-Resource Settings has demonstrated evidence of improving NCD outcomes. Nevertheless, its effectiveness in the Indian settings has not been explored.

About the study

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs), also known as chronic diseases, tend to be of long duration and are the result of a combination of factors

Cariovascular Diseases

Chronic Respiratory Diseases

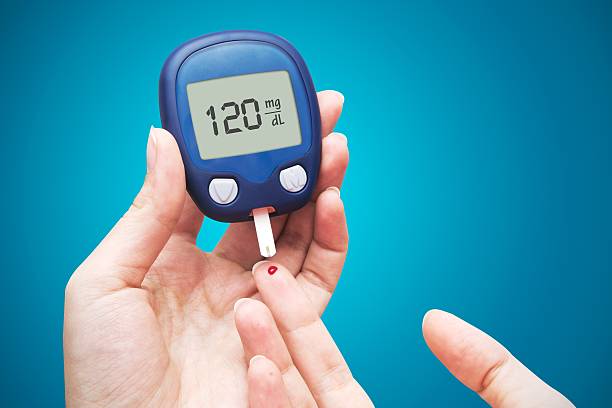

Diabetes

Cancer

What Are Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs)?

- NCDs are medical conditions that are not caused by infectious agents and cannot be spread from one

- person to another.

- They are chronic diseases that usually last for a long time and progress slowly.

- Common examples include:

- Cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks and strokes

- Diabetes mellitus

- Cancers (e.g., lung, breast, cervical)

- Chronic respiratory diseases like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Other significant conditions include mental health disorders, chronic kidney disease, and neurological

disorders (WHO, 2025).

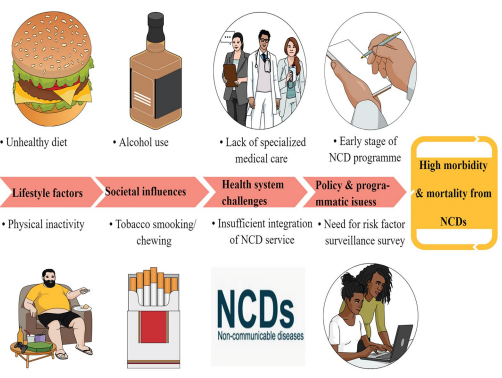

Risk Factors for NCDs

Modifiable Risk Factors:

- Tobacco use: Smoking and tobacco chewing increase risks, especially for lung cancer, heart disease, and COPD.

- Unhealthy diet: High intake of salt, sugar, saturated fats, and low fruit and vegetable consumption.

- Physical inactivity: Sedentary lifestyle contributes to obesity, hypertension, and insulin resistance.

- Harmful use of alcohol: Excessive alcohol intake increases the risk of liver disease, some cancers, and hypertension.

- Environmental factors: Air pollution and exposure to toxic substances contribute to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (Vichitkunakorn et al., 2025).

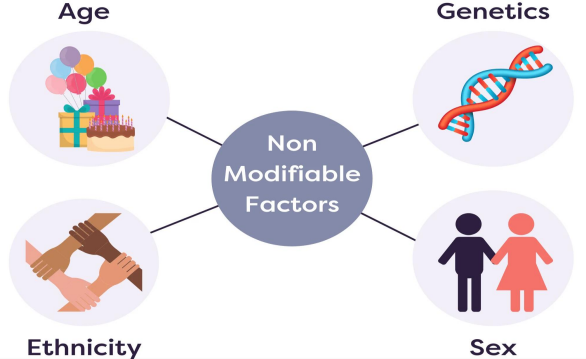

Non-Modifiable Risk Factors:

- Age: As we age our risk of high BP increases. This is due to changes in the heart and blood vessels, whereby there is a loss of elasticity in the tissues found in our arteries. This loss of elasticity results in stiffening and a reduced ability to stretch, leading to increased BP.

- Genetics/Family History: Genetic predisposition plays a role in diseases like diabetes, hypertension, breast cancer, and some heart diseases. Family history can guide early screening (Peltzer et al., 2024).

- Gender: Some diseases are more common in one gender; for example, breast cancer is predominant in women, and prostate cancer in men.

- Ethnicity: People of African and Black Caribbean descent have an increase in the risk of high BP . This is said to be down to genetic predisposition that increases sensitivity to salt in the diet by as little as 1 gram of extra salt per day can increase systolic BP, the pressure exerted on blood vessels when the heart contracts, by as little as much as 5mmHg; the unit of measurement that used when determining BP.

Pressure in your blood vessels is too high (140/90 mmHg or higher). It is common but can be serious if not treated (Hypertension, n.d.)

A chronic condition that occurs either when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or when the body cannot effectively use the insulin it produces (Diabetes, n.d.)

Heart attacks are mainly caused by fatty deposits on the inner walls of the blood vessels that prevents the blood from flowing to the heart. Strokes can be caused due to blood clots or bleeding from blood vessel (Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs), n.d.).

Pressure in your blood vessels is too high (140/90 mmHg or higher). It is common but can be serious if not treated (Hypertension, n.d.)

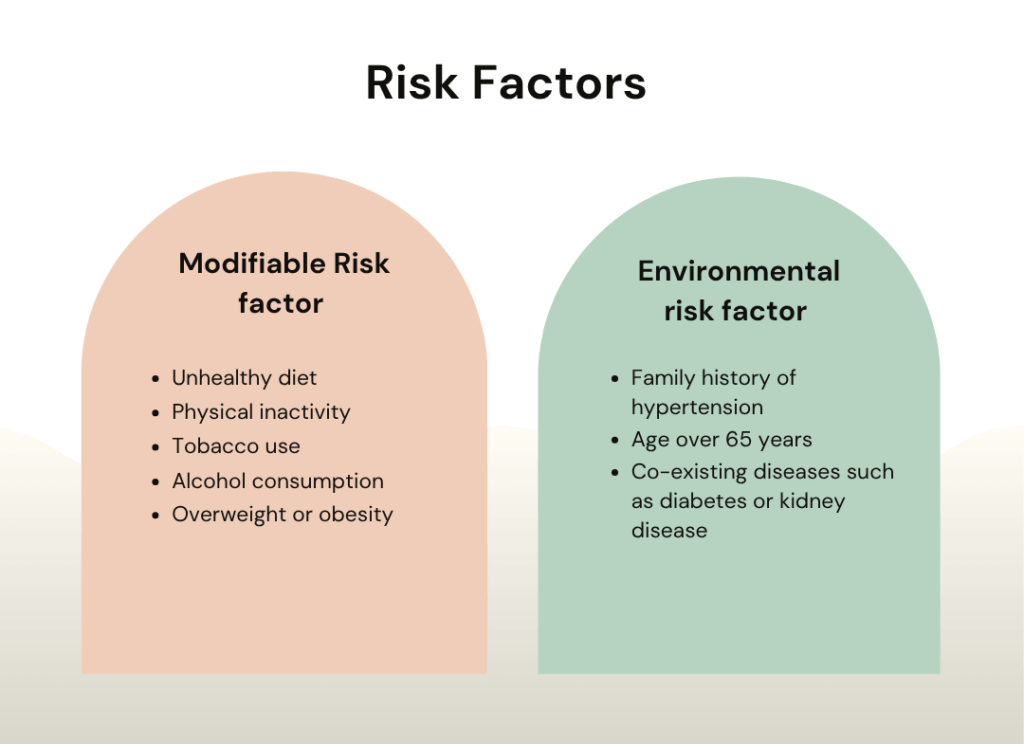

Risk Factors:

| Modifiable Risk factor | Non – Modifiable risk factor |

|---|---|

| Unhealthy diet | Family history of hypertension |

| Physical inactivity | Age over 65 years |

| Tobacco use | Co-existing diseases such as diabetes or kidney disease |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| Overweight or obesity |

A chronic condition that occurs either when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or when the body cannot effectively use the insulin it produces (Diabetes, n.d.)

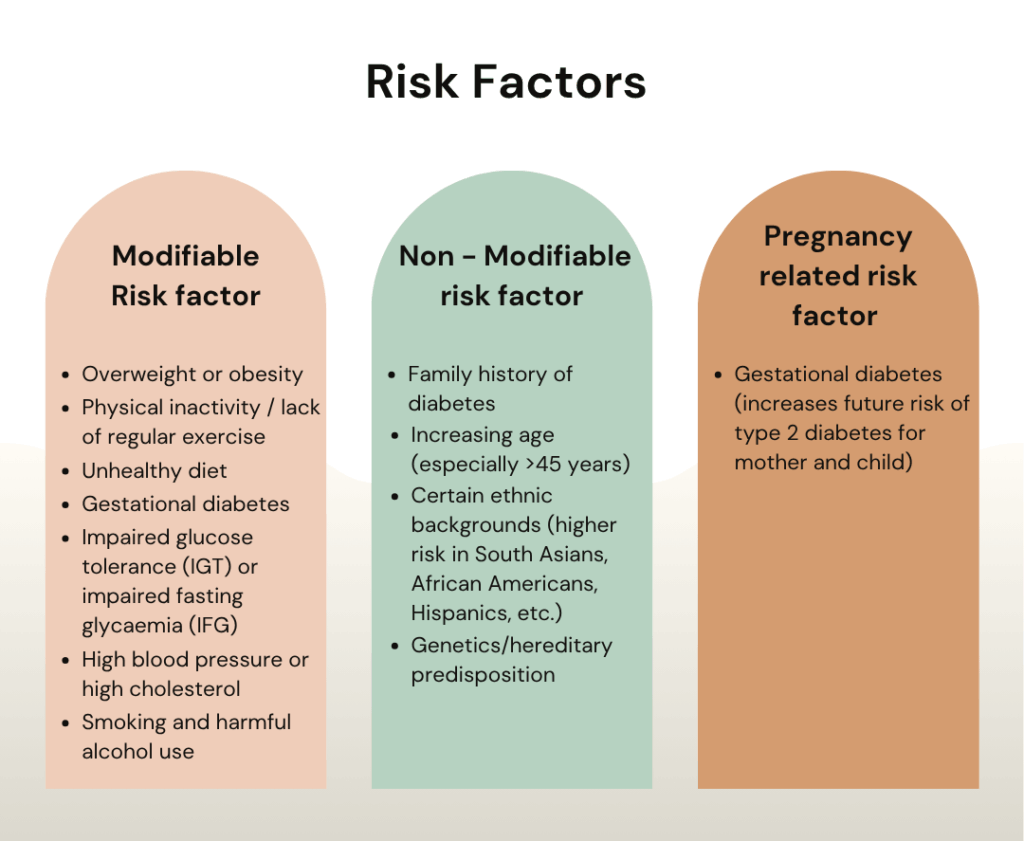

Risk Factors:

| Modifiable Risk factor | Non – Modifiable risk factor | Pregnancy related risk factor |

|---|---|---|

| Overweight or obesity | Family history of diabetes | Gestational diabetes (increases future risk of type 2 diabetes for mother and child) |

| Physical inactivity / lack of regular exercise | Increasing age (especially >45 years) | |

| Unhealthy diet | Certain ethnic backgrounds (higher risk in South Asians, African Americans, Hispanics, etc.) | |

| Gestational diabetes | Genetics/hereditary predisposition | |

| Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or impaired fasting | ||

| Glycaemia (IFG) | ||

| High blood pressure or high cholesterol | ||

| Smoking and harmful alcohol use |

Heart attacks are mainly caused by fatty deposits on the inner walls of the blood vessels that prevents the blood from flowing to the heart. Strokes can be caused due to blood clots or bleeding from blood vessel (Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs), n.d.).

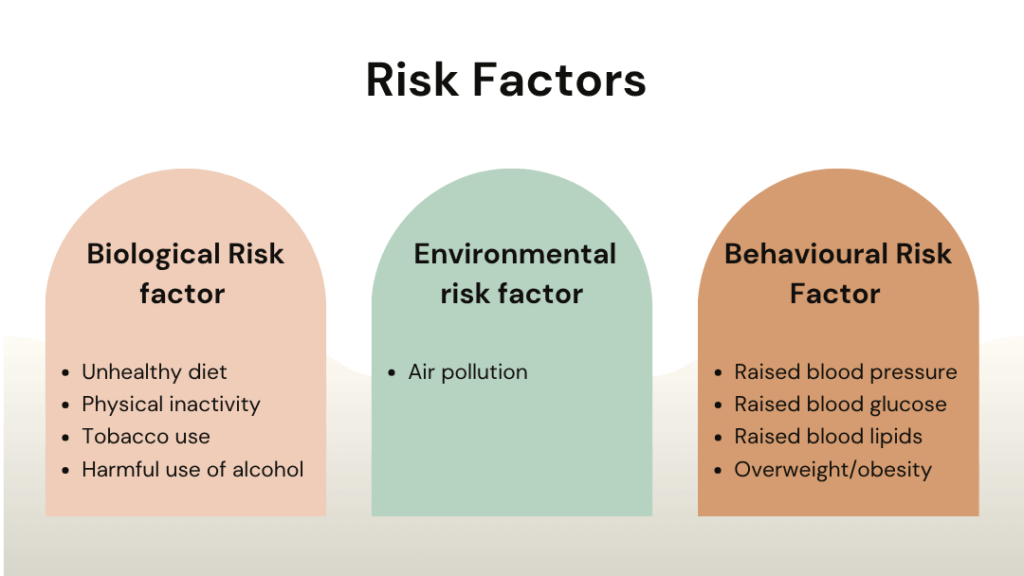

Risk Factors:

| Biological Risk factor | Environmental risk factor | Behavioural Risk Factor |

|---|---|---|

| Unhealthy diet | Air pollution | Raised blood pressure |

| Physical inactivity | Raised blood glucose | |

| Tobacco use | Raised blood lipids | |

| Harmful use of alcohol | Overweight/obesity |

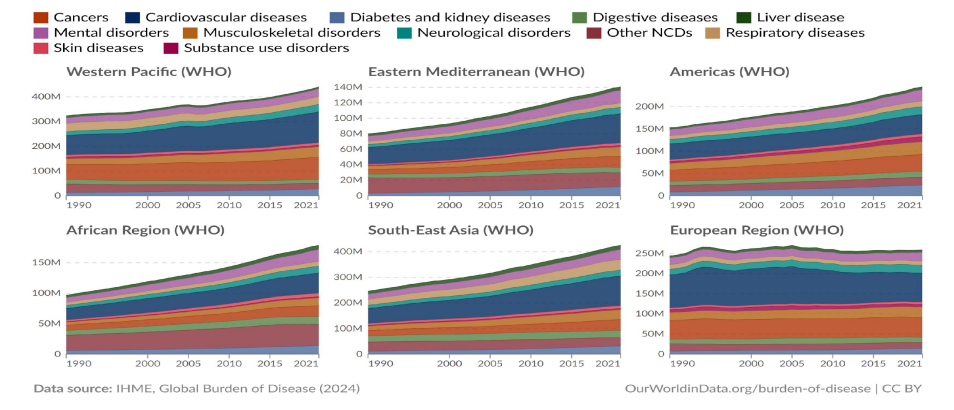

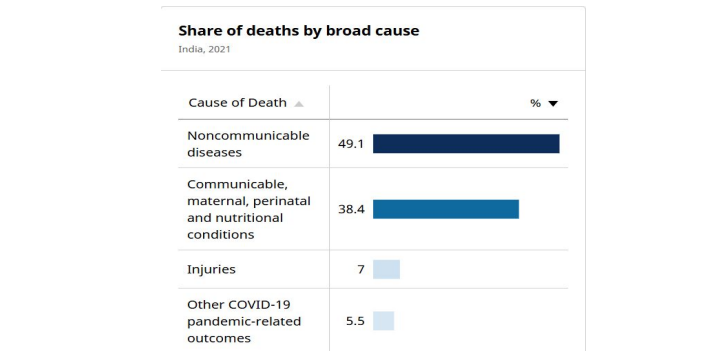

Why this study matters in global health?

Global Burden of NCD

- Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) killed at least 43 million people in 2021, equivalent to 75% of non-pandemic-related deaths globally (Non-communicable Diseases, n.d.-b).

- In 2021, 18 million people died from an NCD before age 70 years; 82% of these premature deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (Non-communicable Diseases, n.d.-b).

- Of all NCD deaths, 73% are in low- and middle-income countries (Non-communicable Diseases, n.d.-b).

- The four major NCD groups account for the bulk of deaths: CVD, cancer, Chronic respiratory disease and Diabetes. These four together explain roughly 80% of premature NCD deaths (Wang et al., 2024).

- In terms of burden beyond deaths, recent GBD analyses report large and rising counts of incident cases and DALYs for many NCDs (Wang et al., 2024).

- Principal modifiable risks are tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, and air pollution (ambient and household). Air pollution is estimated to contribute millions of deaths annually (“Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2023,” 2025)

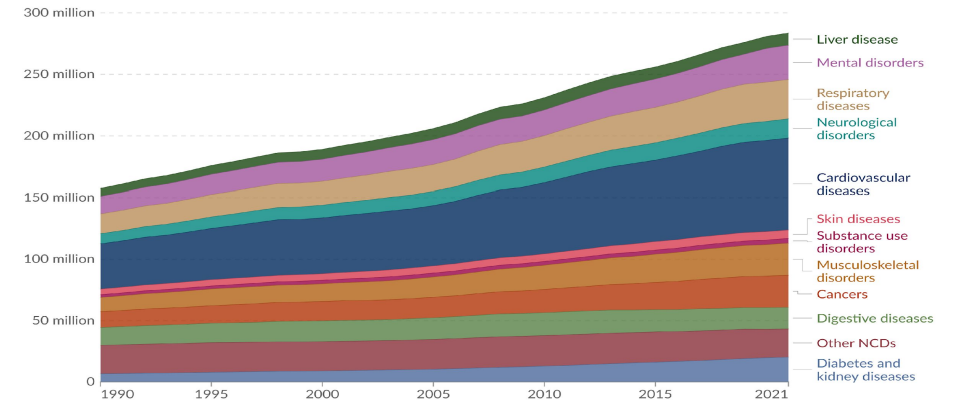

Disease burden from non-communicable diseases, 1990 to 2021

Total disease burden from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), measured in DALYS (Disability-Adjusted Life Years) per year. DALYs are used to measure total burden of disease both from years of life lost and years lived with a disability. One DALY equals one lost year of healthy life.

IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024) – with minor processing by Our World in Data

NCD Burden in India

- The largest single contributors to NCD mortality in India are ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, followed by chronic respiratory diseases, cancers and diabetes-related deaths. IHD alone is the top cause of NCD death and DALYs nationally (India, n.d.).

- Global and India-specific GBD estimates indicate large absolute numbers of NCD deaths and DALYs, and while age-standardized rates for some conditions have declined in places, absolute burden has risen in India because of population growth, ageing and epidemiologic transition (moves from infectious to chronic diseases). Several recent reviews and GBD papers show rising absolute

NCD burden since 1990, with regional heterogeneity across states (Ferrari et al., 2024). - India’s epidemiologic transition is uneven — wealthier/urbanized states often show higher NCD mortality and DALY rates from CVD and cancers, while some poorer states still face double burdens (persistent communicable disease burden plus rising NCDs) (Sharma et al., 2024).

- Major modifiable drivers in India

Disease burden from non-communicable diseases, India, 1990 to 2021

Total disease burden from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), measured in DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Years) per year. DALYs are used to measure total burden of disease – both from years of life lost and years lived with a disability. One DALY equals one lost year of healthy life.

Data source: IHME, Global Burden of Disease (2024)

OurWorldinData.org/burden-of-disease | CC BY

World Health Organization 2025 data.who.int, India [Country overview]. (Accessed on 15 October 2025)

Why Urban Slums?

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease are rising rapidly in India, especially in urban slums where access to primary care, early screening, and health awareness remains limited. Our study focuses on strengthening community-level NCD prevention and management in these low-resource settings.

The WHO Package of Essential NCD Interventions (WHO PEN) offers a cost-effective strategy to improve screening and timely referral for NCDs. However, its implementation in India — particularly in urban slums — is still minimal. At the same time, digital access is increasing even in underserved areas, creating an opportunity to empower communities through mobile and web-based health tools.

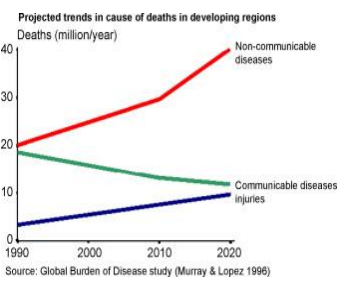

NCD Trends

- The prevalence of obesity has more than doubled among adults between 1990 and 2022, and more than quadrupled among children/adolescents aged 5-19 years (Phelps et al., 2024). Since obesity is a well-established risk factor for many NCDs (especially type 2 diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases, stroke, some cancers, etc.), this surge signals a rising future burden of those NCDs.

- The increase in obesity in children/adolescents is especially steep, meaning NCD risk factors are becoming established earlier in life, raising concerns about earlier onset of NCDs.

- Global counts of NCD deaths and years lived with disability (DALYs) have increased in absolute terms since 1990: many more people now die from NCDs each year because there are more people and more older people worldwide, even where age-standardized rates fall (Abbafati et al., 2020).

- Over recent decades the relative contribution of metabolic and lifestyle risks (unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, obesity, and high blood pressure) has grown — explaining much of the rise in cardiovascular disease and diabetes burden worldwide. Air pollution remains an important environmental driver of cardiovascular and respiratory NCDs, particularly in LMICs.

References

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021). Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Available from https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/.

- Wang, Y., Wang, X., Wang, C., & Zhou, J. (2024). Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Disease, 1990-2021: Results From the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study. Cureus, 16(11). https://doi.org/10.7759/CUREUS.74333

- Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors in 204 Countries and Territories, 1990-2023. (2025). JACC. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JACC.2025.08.015

- Ferrari, A. J., Santomauro, D. F., Aali, A., Abate, Y. H., Abbafati, C., Abbastabar, H., ElHafeez, S. A., Abdelmasseh, M., Abd-Elsalam, S., Abdollahi, A., Abdullahi, A., Abegaz, K. H., Zuñiga, R. A. A., Aboagye, R. G., Abolhassani, H., Abreu, L. G., Abualruz, H., Abu-Gharbieh, E., Abu-Rmeileh, N. M. E., … Murray, C. J. L. (2024). Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet, 403(10440), 2133–2161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8

- Abbafati, C., Abbas, K. M., Abbasi, M., Abbasifard, M., Abbasi-Kangevari, M., Abbastabar, H., Abd-Allah, F., Abdelalim, A., Abdollahi, M., Abdollahpour, I., Abedi, A., Abedi, P., Abegaz, K. H., Abolhassani, H., Abosetugn, A. E., Aboyans, V., Abrams, E. M., Abreu, L. G., Abrigo, M. R. M., … Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet (London, England), 396(10258), 1204–1222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

- Phelps, N. H., Singleton, R. K., Zhou, B., Heap, R. A., Mishra, A., Bennett, J. E., Paciorek, C. J., Lhoste, V. P., Carrillo-Larco, R. M., Stevens, G. A., Rodriguez-Martinez, A., Bixby, H., Bentham, J., Di Cesare, M., Danaei, G., Rayner, A. W., Barradas-Pires, A., Cowan, M. J., Savin, S., … Ezzati, M. (2024). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet, 403(10431), 1027–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02750-2

- Habib, S. H., & Saha, S. (2010). Burden of non-communicable disease: Global overview. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 4(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DSX.2008.04.005

- Health Problems in Urban Slums. (n.d.). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://www.smilefoundationindia.org/blog/health-problems-in-urban-slums/

- Non-communicable diseases. (n.d.-b). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- India. (n.d.-b). Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://data.who.int/countries/356

Tobacco Use and Diabetes & Hypertension

- Tobacco use, both smoked and smokeless, significantly increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and hypertension.

- Smokers have a 30–40% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to non-smokers (Mishra et al., 2022).

- Tobacco promotes insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, worsening glycemic control and accelerating vascular complications (Sakthisankaran et al., 2024; Marbaniang et al., 2021).

- Heavy smoking (e.g., machine-rolled cigarettes) increases hypertension risk significantly (HR: 1.5) (Singh et al., 2022).

- Smokeless tobacco is linked to high blood pressure, especially among women in

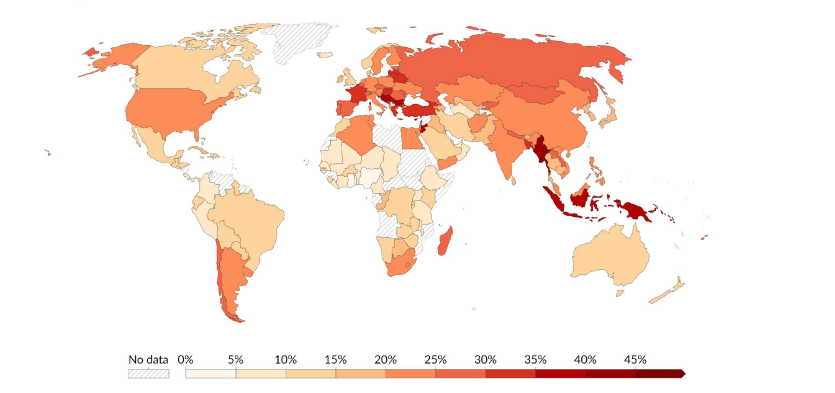

Share of adults who smoke or use tobacco, 2022

Estimated percentage of people aged 15 years and older who currently use tobacco. This includes all forms of tobacco use, such as smoking, chewing or snuffing, but excludes products that do not contain tobacco, such as e-cigarettes.

Data source: World Health Organization – Global Health Observatory (2024)

OurWorldinData.org/smoking | CC BY

Alcohol Use and Diabetes & Hypertension

- Heavy alcohol use increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and worsens glycemic control in diabetics (Piano et al., 2025).

- Each additional drink above 1–2 per day sharply increases the risk of hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke, heart failure, and mortality (Gao et al., 2023; Piano et al., 2025).

- Binge drinking is associated with hypertensive crises and elevated blood pressure (Friesen et al., 2022).

- Adjusted models show alcohol users have 50–130% higher odds of hypertension compared to non-users (Singh et al., 2022).

- Alcohol prevalence in India (NFHS-5, 2019–2021): 17.5% of men and <2% of

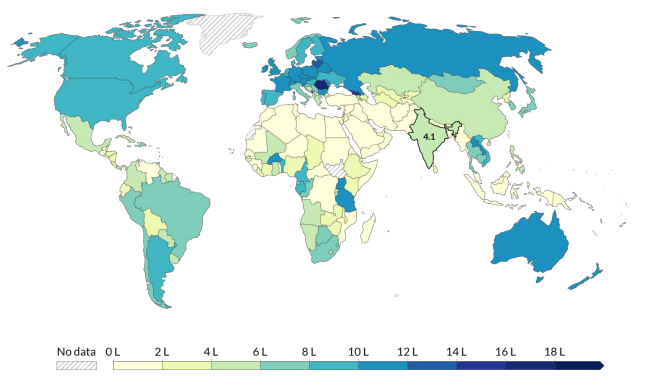

Alcohol consumption per person, 2020

Estimated consumption of alcohol is measured in liters of pure alcohol per person aged 15 or older, per year.

Data source: Global Health Observatory Data Repository-World Health Organization (WHO), via World Bank (2025)

OurWorldinData.org/alcohol-consumption | CC BY

Global Health Observatory Data Repository – World Health Organization (WHO), via World Bank (2025)-processed by Our World in Data

Tobacco & Alcohol Use and Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD)

- Tobacco is an independent, dose-dependent risk factor for all forms of CVD, including heart attack, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease (Piano et al., 2025).

- Heavy smoking with hypertension markedly increases CVD mortality (Kumar et al., 2021).

- Alcohol has a J-shaped relationship with CVD risk: low-moderate intake may reduce

CAD risk, but heavy/binge drinking worsens outcomes (Blomster et al., 2014; Piano et al., 2025). - Tobacco cessation and alcohol moderation are key to reducing CVD risk in diabetic

and hypertensive patients (Kumar et al., 2021).

References

- Data Page: Share of adults who smoke or use tobacco”, part of the following publication: Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2023) – “Smoking”. Data adapted from World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250925-232706/grapher/share-of-adults-who-smoke.html [online resource] (archived on September 25, 2025).

- Data Page: Total alcohol consumption per capita. Our World in Data (2025). Data adapted from Global Health Observatory Data Repository – World Health Organization (WHO), via World Bank. Retrieved from https://archive.ourworldindata.org/20250916-102301/grapher/total-alcohol-consumption-per-capita-litres-of-pure-alcohol.html [online resource] (archived on September 16, 2025).

- Blomster, J. I., Zoungas, S., Chalmers, J., Li, Q., Chow, C. K., Woodward, M., Mancia, G., Poulter, N., Williams, B., Harrap, S., Neal, B., Patel, A., & Hillis, G. S. (2014). The Relationship Between Alcohol Consumption and Vascular Complications and Mortality in Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care, 37(5), 1353–1359. https://doi.org/10.2337/DC13-2727

- Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds)

- Diabetes. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

- Friesen, E. L., Bailey, J., Hyett, S., Sedighi, S., de Snoo, M. L., Williams, K., Barry, R., Erickson, A., Foroutan, F., Selby, P., Rosella, L., & Kurdyak, P. (2022). Hazardous alcohol use and alcohol-related harm in rural and remote communities: a scoping review. The Lancet Public Health, 7(2), e177–e187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00159-6

- Gao, N., Liu, T., Wang, Y., Chen, M., Yu, L., Fu, C., & Xu, K. (2023). Assessing the association between smoking and hypertension: Smoking status, type of tobacco products, and interaction with alcohol consumption. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 10, 1027988. https://doi.org/10.3389/FCVM.2023.1027988/BIBTEX

- Hypertension. (n.d.). Retrieved September 29, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension

- Kumar, R., Kant, S., Chandra, A., & Krishnan, A. (2021). Tobacco use and nicotine dependence among patients with diabetes and hypertension in Ballabgarh, India. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease, 92(1). https://doi.org/10.4081/monaldi.2021.1799

- Marbaniang, S. P., Lhungdim, H., Chauhan, S., & Srivastava, S. (2021). Interaction of multiple risk factors and population attributable fraction for type 2 diabetes and hypertension among adults aged 15–49 years in Northeast India. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 15(5), 102227. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DSX.2021.102227

- Mishra, V. K., Srivastava, S., Muhammad, T., & Murthy, P. V. (2021). Population attributable risk for multimorbidity among adult women in India: Do smoking tobacco, chewing tobacco and consuming alcohol make a difference? PLOS ONE, 16(11), e0259578. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0259578